Alright, let’s talk about Monty Python and the Holy Grail. As a filmmaker and a full-time colorist, this film has always held a special place for me. It’s not just a comedic masterpiece; it’s a brilliant case study in how severe limitations can breed incredible creativity and forge a truly unique visual identity. You look at the final product this iconic, endlessly quotable film and it’s easy to forget the sheer “agony of filming it,” as the Pythons themselves described it. But for me, the visual language, born out of necessity and a complete disregard for traditional filmmaking norms, is just as fascinating as the jokes.

It’s often touted as a “rock and roll miracle” because its funding came from bands like Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin rather than traditional studios. That kind of independent backing gave them an almost anarchic freedom, but it didn’t come with a blank check. Quite the opposite. The budget was so restrictive—around $400,000, which was tight even for 1975 that every single creative decision was a direct response to financial realities. And that is where the real genius lies.

About the Cinematographer

The person tasked with capturing this glorious mess on film was Terry Bedford. While Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones tag-teamed the directing duties, with Gilliam often pushing for a grander visual scope, it was Bedford’s eye that translated their vision into moving images. He wasn’t just pressing record; he was constantly problem-solving.

Bedford’s role was a baptism by fire. He had to contend with the Scottish Department of the Environment denying access to pre-scouted castles, forcing the production to rely almost entirely on the privately-owned Doune Castle. Imagine this: on the very first day of shooting, the camera jams on the first take, and they have to finish the day without a sound camera. As a DP, you have to be adaptable, but that is next-level stress. There are stories of the producer trying to cut corners by buying six-year-old film stock, and Bedford literally tossing it into a stream in protest. That’s a testament to a cinematographer who fought for image quality, ensuring that the visual absurdity was grounded in a tangible, gritty reality.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The cinematic inspiration for Holy Grail wasn’t some grand European art film or a classic Hollywood epic. It was pure, unadulterated Python. Their approach to comedy was always about subverting expectations, and the cinematography followed suit. Gilliam himself noted that “if you maintain a low standard of production from the start, you can get away with anything.” It’s not about being bad; it’s about establishing a visual grammar where the ridiculous feels at home.

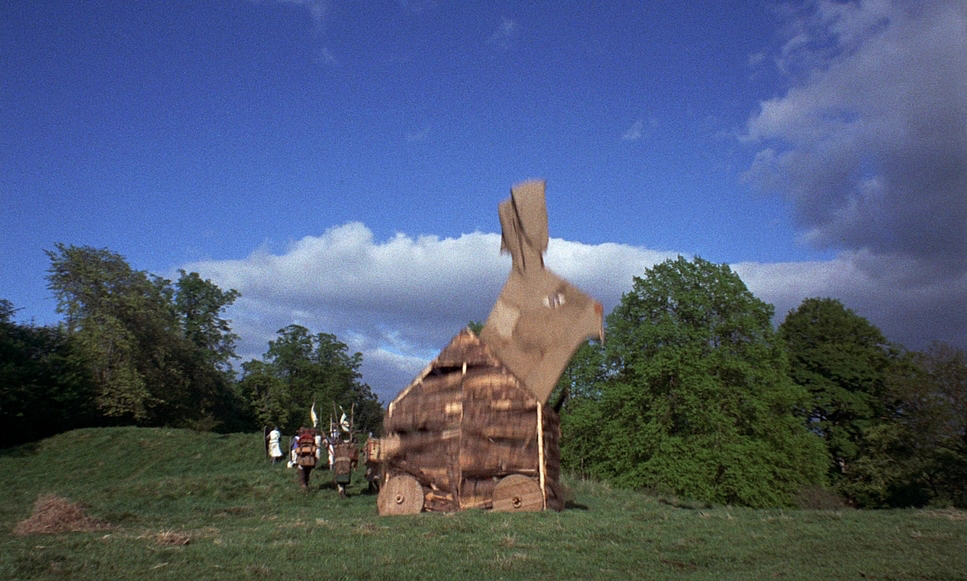

The original script called for real horses and massive battles. But when the budget hit, that reality evaporated. The coconuts weren’t just a funny gag; they were a budgetary necessity. This directly informed the visual style: instead of sweeping shots of charging cavalry, you got wide shots of knights “galloping” on foot through the mud. It immediately sets a tone that says, “we’re not taking ourselves seriously, and neither should you.” This conscious decision to embrace the low-fi aesthetic became the film’s visual signature, leveraging the stark, often dreary Scottish landscape as a backdrop for their bizarre antics.

Camera Movements

When you watch Holy Grail, you immediately notice the pacing. The filmmakers adopted a style that was “long, wide, and uninterrupted.” This wasn’t just an aesthetic choice; it was deeply economical. As a colorist, I always think about how cutting patterns influence pacing. Here, the extended takes meant fewer setups, less time moving the camera, and less film stock burnt—critical for a shoestring budget.

This approach feels akin to stage work, which fits the Pythons’ background perfectly. It allowed the comedic timing to play out organically within the frame. There aren’t many quick cuts or intense close-ups punctuating every punchline. Instead, the camera hangs back, letting the absurdity unfold. Think of the scene with the dim-witted guards: “Make sure the prince doesn’t leave this room until I come and get it.” That entire exchange plays out in a master shot, preserving the rhythm of the dialogue. It forces the audience to observe the full tableau, making the bizarre behavior feel even starker against the environment. It puts immense pressure on the performances, but it totally pays off.

Compositional Choices

The film’s compositional strategy was heavily influenced by its constraints. With limited locations—primarily Doune Castle and the unforgiving Scottish countryside

they had to be incredibly resourceful. They used clever framing to create the illusion of different interior and exterior locations at the same castle, rotating rooms or shifting the camera ten feet to present a “new” setting. This requires a keen eye for how each frame isolates elements to maintain the illusion.

The wide shots serve multiple purposes. They establish the bleak scale of the Highlands, contrasting beautifully with the silliness unfolding within. It creates a stage where the absurd drama plays out against a formidable natural backdrop. These compositions often employ deep focus, keeping foreground characters and background elements sharp, allowing visual gags to occur on different planes simultaneously. When Arthur’s “army” appears at the end a mere 175 university students the wide shots paradoxically emphasize their lack of numbers, creating a visual joke out of the disparity between expectation and reality.

Lighting Style

The lighting in Monty Python and the Holy Grail is refreshing in its honesty. Given the budget and the notoriously fickle Scottish weather, much of the film relies on natural, ambient light. We know the “light vanished” on the first day and costumes soaked through with rain, which tells you elaborate lighting setups were a luxury they couldn’t afford.

What you get is a soft, diffused quality from overcast skies, or the direct, hard light of a rare sunny moment. This naturalistic approach grounds the fantastical elements. The drab, desaturated look of the environment makes the vibrant splashes of Gilliam’s animations, or props like the Holy Hand Grenade, pop with impact. As a colorist, I appreciate the purity of this capture. It leaves room to subtly sculpt the mood in post without fighting artificial sources. While Gilliam is famous for his obsession with atmosphere often joking about “Gilliams” as a unit of measurement for on-set smoke the goal was likely adding texture and depth to the existing light rather than radically shaping it.

Lensing and Blocking

The choice of lensing works hand-in-hand with the long takes. Bedford likely relied on standard spherical primes (like Cookes or Zeisses of that era) for most shots. These focal lengths naturally keep more elements in focus, which was crucial for those extended takes where multiple actors needed to be visible simultaneously. The glass from that era offered a more organic, slightly softer fall-off than modern super-sharp lenses, contributing to the film’s period feel.

Blocking became a choreography challenge. With the Pythons playing multiple roles John Cleese juggled Lancelot, the French Taunter, and Tim the Enchanter precise blocking was paramount. “You couldn’t do one shot because John had to be somebody else,” as the story goes. This meant planning movements to minimize costume changes or allow for camera repositioning. The static camera placed the onus on the actors to move into and out of compositions, using the full depth of the frame for entrances and reveals.

Color Grading Approach

Now, let’s put on my colorist hat. If I were sitting in the suite with the original negative scans today, the goal would be to respect the print-film sensibilities of 1975 warmer shadows, soft highlight rolls, and that distinct grain structure. A modern temptation might be to “clean it up” or use power windows to brighten faces, but that would kill the vibe.

My approach would focus on density and texture. We’d start with a film print emulation LUT to establish that baseline contrast, ensuring those cold, muddy Scottish landscapes have sufficient weight without crushing the blacks entirely. You want the grimy textures of their “knitted string” chainmail to feel palpable. I would likely use a subtractive color model to handle the saturation; when the film gets dark or gritty, the colors shouldn’t feel digital or electric.

Hue separation is critical here. The palette is dominated by muted greens and browns. I’d want to push some cyan into the mid-shadows to emphasize the dampness the cast endured, while keeping the skin tones slightly separate so the actors don’t disappear into the mud. It’s about finding the balance between a robust contrast and the gentler highlight roll-off of 70s stock. You want the viewer to subconsciously feel the cold wind of Scotland in May.

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Monty Python and the Holy Grail – Technical Specs | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Adventure, Comedy, Fantasy, Parody, Slapstick, Medieval |

| Director | Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones |

| Cinematographer | Terry Bedford |

| Production Designer | Roy Forge Smith |

| Costume Designer | Hazel Pethig |

| Editor | John Hackney |

| Time Period | Medieval: 500-1400 |

| Color | Cool, Desaturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.66 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Soft light, Low contrast |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | United Kingdom > Britain |

| Filming Location | Stirling > Doune |

| Camera | Arriflex BL |

The technical reality of Holy Grail is a testament to pushing limits. Starting with just $400,000, they faced “challenge after challenge.” One sound camera that jammed. A handful of umbrellas for the whole crew. Wool chainmail that absorbed rain until the actors were freezing. These aren’t just anecdotes; they are tangible obstacles that shaped the final image.

The necessity to move quickly meant shooting the whole thing in about five weeks. This speed, combined with the directors’ inexperience, meant the overtime budget was blown immediately, injecting a chaotic, improvisational energy into the film.

Even the famous “Black Beast of Arrrghhh” scene was a technical workaround. In the movie, the scene ends because the “animator suffers a fatal heart attack.” While on screen this plays as a hilarious meta-joke, in production reality, it was a brilliant way to end a sequence they didn’t have the budget or time to animate fully. The “book of the film” transitions were similarly ingenious ploys to cover narrative gaps without shooting live action. Every creative flourish emerged directly from scarcity, proving that in filmmaking, constraint is often the most fertile ground for innovation.

- Also read: CASINO (1995) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: L.A. CONFIDENTIAL (1997) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →