Hi, I’m Salik Waquas—a full-time film colorist and the proud founder of Color Culture. My world is one where every shade, contrast, and nuance breathes life into the celluloid dreams we call films. With my heart steeped in classic cinema and my eyes trained on the subtleties of light and shadow, I invite you to join me on this article where I break down the cinematography of Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

About the Cinematographer

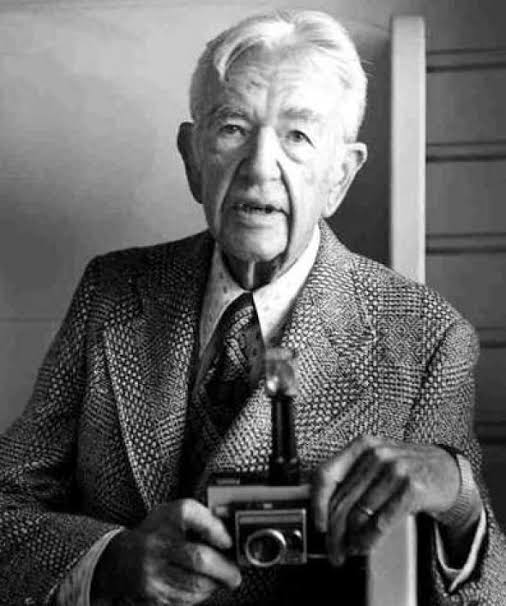

When we speak of the cinematographers behind The Great Dictator, names like Karl Struss and Roland Totheroh immediately come to mind. These maestros of the camera lens shaped a film that is as rich in technical prowess as it is in subversive satire. I first encountered their work when I ventured into the realm of silent films—having been charmed by Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. and the delightful antics of The General.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of “The Great Dictator”

I remember the day I sat down to watch The Great Dictator like it was yesterday—a day marked by curiosity, a dash of serendipity, and a hearty serving of cinematic rebellion. Initially, I sought out classic films as a means to explore the depths of silent comedy. Yet, when I encountered Chaplin’s work, I was swept off my feet by a film that defied simple categorization. It was as if the camera, under Chaplin’s ingenious direction, became a window to a world where laughter and sorrow danced in unison.

The inspiration for the cinematography of this film is rooted in a time when the world teetered on the edge of darkness. In 1940, as the Allies grappled with the Axis menace and America remained suspiciously perched on the sidelines, Chaplin’s lens pierced through the veil of nationalistic isolation. His goal was to rally sympathy for the persecuted—most notably the Jewish victims of fascist tyranny—and to expose the ludicrous nature of dictatorial power. I found that Chaplin’s use of the camera was less about creating mere images and more about forging a political statement. The globe scene, where the titular dictator toils with a toy-like representation of the world, is a metaphor so potent that it continues to reverberate even today. It’s a playful yet piercing reminder that power, when unchecked, turns the world into nothing more than a prop in the hands of the despotic.

This duality—where humor meets gravity—is what inspired me to delve deeper into the film’s visual lexicon. The camera is not just an observer; it’s an active participant in the narrative, subverting the dominant ideologies of its time while reminding us of the power of kindness and bravery. For me, this cinematic inspiration is a clarion call: to always seek truth behind the lens, no matter how absurd or whimsical the world might appear.

Camera Movements Used in The Great Dictator

I was particularly taken by the globe scene—a moment where Chaplin’s character, with a playful smirk, caresses a spinning world as if it were a mere bauble. This isn’t just a clever shot; it’s an embodiment of power reduced to a child’s game. The camera movements in this scene—smooth, unhurried, yet profoundly intentional—invite the viewer to question the nature of control and the absurdity of absolute power. Even the slightest shift in angle or focus acts as a subtle nod to the idea that the world, in the hands of a tyrant, is nothing more than a toy to be manipulated at will.

Compositions In The Great Dictator

In The Great Dictator, every frame is meticulously crafted, as if each shot were a carefully arranged still-life painting. The compositions are nothing short of revolutionary—placing the victims of tyranny in the foreground while relegating the caricatured dictators to the periphery of the frame.

Chaplin’s genius lies in his ability to convey layered narratives through visual design. In one frame, a Jewish barber’s plight is rendered with such intimacy that it demands our empathy, while in another, the absurdity of authoritarian rule is laid bare through the exaggerated features of a dictator. The compositions in this film are a masterful blend of artistry and ideology; they are designed to strip away the veneer of political rhetoric and reveal the raw, unfiltered humanity beneath.

For me, as someone whose life revolves around color and composition, this film is a vibrant canvas where every element—every shadow, every highlight, every carefully considered space—speaks volumes.

Lighting Style of The Great Dictator

Chaplin’s approach to lighting is both subtle and expressive. Soft, diffused lighting often bathes the scenes depicting the everyday struggles of the oppressed, imbuing them with warmth and a fragile hope. In contrast, the harsh, almost theatrical lighting that falls upon the buffoonish dictators accentuates their grotesque features and underscores the absurdity of their power. The deliberate use of high contrast is not just a technical decision—it’s an ideological one. It draws the viewer’s attention to the stark dichotomy between benevolence and tyranny, between light and darkness, both literally and metaphorically.

In my work as a film colorist, I find that such lighting choices are the true soul of a film’s aesthetic. They breathe life into the narrative, evoking emotions that resonate on a deeply personal level. The lighting in The Great Dictator is a testament to the power of subtlety—a reminder that sometimes, the quietest elements can speak the loudest truths.

Lensing and Blocking of The Great Dictator

The film’s blocking is a brilliant interplay between the heroic and the absurd. For instance, the close-ups of the Jewish barber’s earnest eyes contrast sharply with the wide, exaggerated shots of the bumbling dictators. Chaplin’s meticulous arrangement of characters within each frame serves to underscore their roles—heroes versus buffoons, the oppressed versus the oppressors. The lens, then, becomes a kind of moral arbiter, drawing our attention to those who suffer and relegating the tyrants to the role of comic relief.

Color of The Great Dictator

| Genre | Comedy |

| Director | Charlie Chaplin |

| Cinematographer | Karl Struss, Roland Totheroh |

| Production Designer | J. Russell Spencer |

| Costume Designer | Ted Tetrick |

| Editor | Willard Nico |

| Time Period | 1930s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.33 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | … Earth > Europe |

| Filming Location | … California > Los Angeles |

Now, you might wonder how color plays a role in a film that is, at its core, a black-and-white masterpiece. Yet, even in the absence of literal color, the film is awash in a vibrant spectrum of contrast, texture, and emotion. Here, color isn’t just about pigments—it’s about the mood, the tone, and the subtle cues that guide our interpretation.

Every grayscale gradient in The Great Dictator is a deliberate choice—a chiaroscuro palette that transforms simple hues into powerful symbols. The stark blacks and brilliant whites are used to create a visual language that speaks of dualities: good versus evil, hope versus despair, humor versus tragedy. As I work with color in my daily life, I marvel at how even in a monochromatic scheme, one can evoke a riot of emotions. The “color” of this film lies in its texture—the interplay of light, shadow, and form that gives it a timeless quality, a vibrancy that transcends the absence of color.

- Also Read: Cinematography Analysis Of Marketa Lazarová (In Depth)

- Also Read: Cinematography Analysis Of Anora (In Depth)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →