As a filmmaker and colorist running my own post-production color grading suite, I have always been fascinated by the intricate dance between visuals and storytelling. The way light, shadow, and color interplay to evoke emotion is a craft that continually inspires me. One film that has profoundly impacted my perspective is Jonathan Demme’s “Stop Making Sense,” a concert film that transcends its genre through innovative cinematography.

About the Cinematographer

The visual brilliance of “Stop Making Sense” is largely attributable to Jordan Cronenweth, a cinematographer whose work has left an indelible mark on cinema. Known for his atmospheric and emotionally resonant visuals in films like “Blade Runner,” Cronenweth brought a unique sensibility to this project. His collaboration with director Jonathan Demme and Talking Heads frontman David Byrne resulted in a concert film that feels more like a cinematic journey than a mere recording of live performances.

Working closely with Byrne, Cronenweth crafted visuals that were both intimate and expansive. Their shared vision was to elevate the concert experience into an art form, using the camera not just to document but to narrate. The synergy between Cronenweth’s technical prowess and Byrne’s conceptual ideas created a film that is as much about visual storytelling as it is about music.

Inspiration for the Cinematography of “Stop Making Sense”

What sets “Stop Making Sense” apart from other concert films is its departure from conventional formulas. Drawing inspiration from classic musicals, minimalist art, and even German expressionist cinema, the film embraces a theatrical approach to lighting and set design. David Byrne’s role as a lighting designer was pivotal; he envisioned lighting as a storytelling device rather than mere illumination.

Cronenweth and Byrne’s collaboration led to the use of dramatic contrasts and chiaroscuro techniques, reminiscent of film noir aesthetics. This high-contrast lighting, utilizing silhouettes and shadows, resonates with themes of identity and transformation present in the band’s music. The result is a cinematic experience where each song becomes a visual chapter, contributing to an overarching narrative.

Camera Movements Used in “Stop Making Sense”

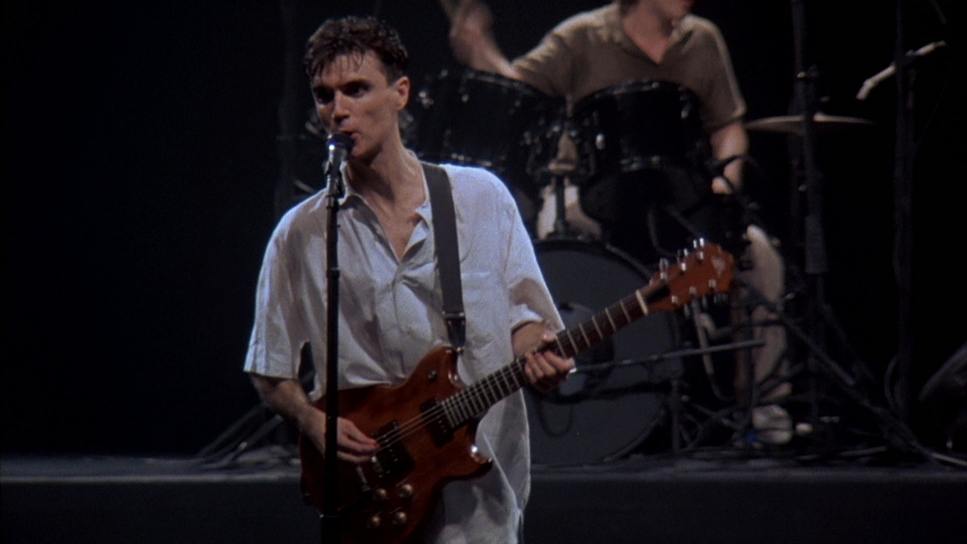

The camera movements in the film are meticulously choreographed to enhance the performance rather than distract from it. The opening shot sets the tone—a tracking shot follows Byrne’s feet as he steps onto the bare stage for “Psycho Killer,” eventually revealing his face as he begins to sing. This immersive perspective draws the audience into the performance from the very beginning.

In songs like “Once in a Lifetime,” the camera holds steady in a medium shot for extended periods, allowing Byrne’s eccentric choreography to captivate without interruption. This technique harkens back to the methods of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, who favored unbroken takes to showcase dance. Elsewhere, subtle handheld movements and dynamic panning follow the performers, creating an intimate connection between the viewer and the stage.

Compositions in “Stop Making Sense”

The film’s compositions are a study in deliberate framing and spatial dynamics. Cronenweth often employs asymmetrical framing to emphasize the interaction between the band members and their environment. During “What a Day That Was,” for example, upward lighting transforms Byrne’s face into a haunting mask, reinforcing the song’s existential themes.

In “This Must Be the Place,” the band gathers under the soft glow of a single lamp at the front of the stage, creating an intimate scene that feels almost like a gathering among friends. The use of negative space and shadows adds to the minimalist aesthetic, drawing focus to the performers and their emotive expressions.

Lighting Style of “Stop Making Sense”

Lighting in “Stop Making Sense” goes beyond functional necessity; it becomes a central narrative element. Each song features a unique lighting design that aligns with its emotional tone. Byrne’s innovative approach often involves extreme contrasts—bright lights isolating performers against dark backgrounds, creating a stark and impactful visual.

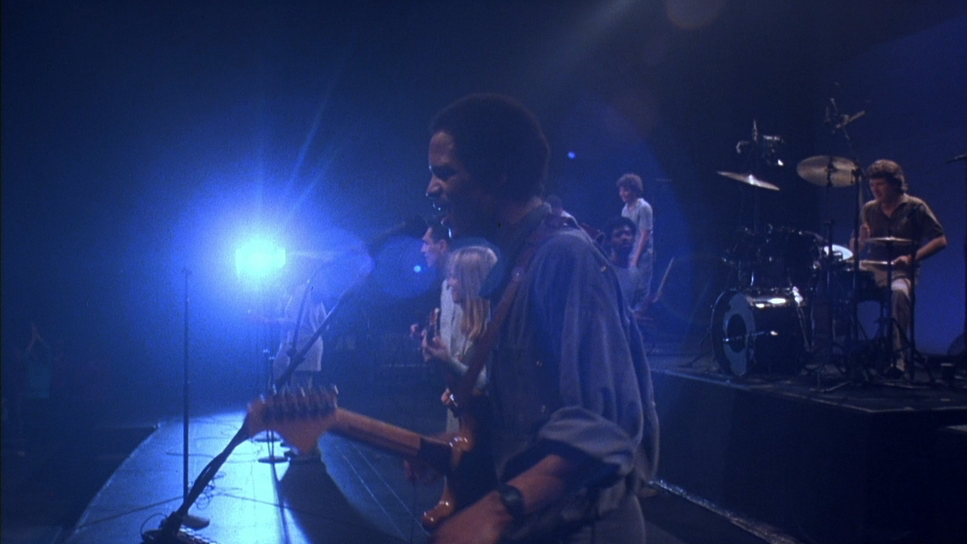

One of the most striking examples is during “What a Day That Was,” where dramatic upward lighting casts intense shadows, giving Byrne an almost otherworldly appearance. In contrast, “Psycho Killer” uses even, high-key lighting to create a sense of exposure and vulnerability. The strategic use of silhouettes, particularly in “Take Me to the River,” adds an ethereal quality to the performance, enhancing the emotional depth.

Lensing and Blocking of “Stop Making Sense”

Cronenweth’s choice of lenses and the meticulous blocking of scenes contribute significantly to the film’s immersive feel. By using medium and close-up lenses, the performers are brought into the viewer’s personal space, highlighting subtle expressions and movements. The introduction of Byrne’s oversized suit later in the performance becomes a visual spectacle, captured through wide frames that emphasize its exaggerated proportions.

The blocking is carefully planned to reflect the evolving dynamics on stage. The gradual addition of band members in the opening songs creates a sense of progression, both musically and visually. This deliberate staging enhances the narrative flow, making the audience feel as if they’re part of a developing story.

Color of “Stop Making Sense”

Color in the film is used sparingly but effectively. The predominantly monochromatic palette serves to focus attention on the performers, while strategic bursts of color underscore emotional shifts. Deep blues during “Take Me to the River” evoke a sense of depth and introspection, while warmer tones in “This Must Be the Place” create a cozy, intimate atmosphere.

Cronenweth’s restrained use of color ensures it complements rather than overpowers the performance. This subtlety adds layers to the visual narrative, enhancing the emotional resonance without distracting from the music.

Technical Aspects: Cameras, Lenses, and More

| Genre | Music, Documentary, Concert Film |

| Director | Jonathan Demme |

| Cinematographer | Jordan Cronenweth |

| Costume Designer | Laura Langdon, Gail Blacker |

| Editor | Lisa Day |

| Colorist | Scot Olive |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | Los Angeles > Pantages Theater |

| Filming Location | Los Angeles > Pantages Theater |

| Camera | Panavision Panaflex |

| Lens | Panavision Lenses |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 4K |

From a technical standpoint, “Stop Making Sense” is a feat of precision and innovation. Filmed over four performances at the Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles, the production seamlessly weaves together footage to create a cohesive experience. This required consistent lighting and framing to make transitions between different nights imperceptible.

An intentional choice was made to minimize audience shots, a departure from typical concert films. This keeps the focus squarely on the performers, drawing the viewer deeper into the on-stage world. When the audience is shown, it’s done strategically to amplify the energy during climactic moments, such as in “Cross-Eyed and Painless.”

The editing aligns with the tempo and mood of each song. Extended takes are used to let performances breathe, while rapid cuts heighten the energy during more frenetic numbers. The analog equipment and thoughtful lens choices contribute to an authentic and unobtrusive capture of the live experience.

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF THE WAGES OF FEAR (IN DEPTH)

- Also Read: CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS OF IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (IN DEPTH)

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →