Tony Scott’s Man on Fire (2004) the technical and the emotional are inseparable. It’s a masterclass in how aggressive, intentional cinematography can stop being a “choice” and start becoming a character in its own right, pushing the audience right into the fractured psyche of its protagonist.

Look, this isn’t just another Denzel Washington action flick. It’s a top-tier performance where he goes from a hollowed-out soul to a brutal avenger, and Dakota Fanning… man, that kid’s performance is what makes the whole thing hurt. But as a visual storyteller, what keeps me coming back is how unapologetically bold this film is. It’s gritty, it’s stylish, it’s confrontational. Let’s pull back the layers on how Paul Cameron and Tony Scott actually pulled this off.

About the Cinematographer

The man behind the glass was Paul Cameron. If you don’t know the name, you’ve definitely felt his energy. Cameron has this specific visual signature a mix of grounded realism and hyper-stylized energy. He’s the kind of DP who isn’t afraid to let the highlights burn or let the shadows go muddy if it serves the vibe. Before Man on Fire, he’d already cut his teeth on Gone in 60 Seconds and Swordfish, showing he could handle high-octane sleekness. But it was his work here, and later his collaboration with Michael Mann on Collateral, that really cemented him as a guy who views the camera not just as a recorder, but as an active, breathing participant in the narrative.

Color Grading Approach

I’m jumping straight to the grade because, for me, this is where the movie’s soul lives. In 2004, the Digital Intermediate (DI) workflow was still the “new frontier,” and Ryan Pannell (the colorist) used it to push boundaries that most people were scared of. We’re talking about a look that defines “grungy and gritty.”

As a colorist, I look at this and see a massive amount of contrast shaping. They weren’t afraid to “crush” the blacks, creating this heavy, oppressive weight in the shadows during Creasy’s low points. But the real magic is the hue separation. They leaned into that “cross-processed” look taking color reversal stocks like the Kodak 5285 and 5239and pushing them to the limit. It gives you those hot, electric yellows in the Mexico City sun and those deep, bruised cyans and blues in the night scenes. It’s not “natural,” but it feels real because it mirrors the feverish, high-stakes atmosphere of the city.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Tony Scott was never a “play it safe” director. For Man on Fire, the North Star was clearly the Brazilian masterpiece City of God. If you’ve seen that film, you know it’s a whirlwind of 16mm chaos and documentary-style immediacy. Scott and Cameron took that lesson to heart.

The mission wasn’t to just “show” Mexico City; it was to make you feel the suffocating heat and the constant, low-level hum of danger. They wanted a visual language that felt like it was decaying but still beautiful. This led them to embrace oversaturated palettes and a camera that feels like it’s constantly looking over its shoulder. It says, “This place is alive, and it might just kill you,” which is the perfect headspace for Creasy’s descent into the abyss.

Technical Aspects & Tools

To get that raw texture, they didn’t just stick to one format. They mixed Super 35mm with 16mm reversal. Using workhorse cameras like the Arri 2C and Panavision Millenniums for the heavy lifting, and then jumping to the Aaton Aminima (a tiny, handheld 16mm rig) for those frantic, “get-in-there” moments.

They were shooting on a variety of Kodak Vision stocks 500T (5229) for that grainy, moody interior feel and 200T (5274) for the exteriors. By using Color Reversal 160D and 100D, they achieved that “blown-out” look where the highlights don’t just clip they glow. They used Panavision Primo glass, but Cameron wasn’t afraid to throw a long lens on to compress the frame, making the city feel like it was closing in on the characters.

Camera Movements

The movement in this film is… well, it’s polarizing. Scott used this rapid-fire, “shaky-cam” approach that some people find jarring. But in Man on Fire, it’s perfectly calibrated. It’s not just “cool” movement; it’s psychological.

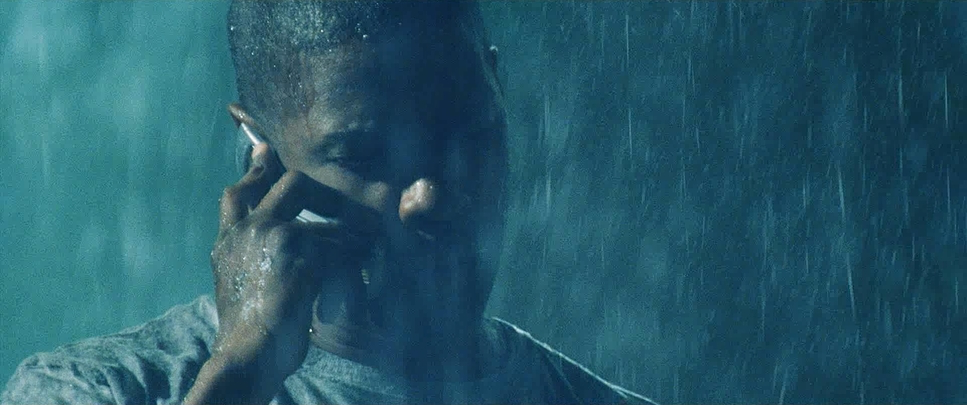

Early on, when Creasy is drunk and lost, the camera is a bit more sluggish, reflecting his weary state. But once Lupita is taken, the leash comes off. We get aggressive handheld work, whip pans that feel like a physical jolt, and those iconic “crash zooms” that thrust you into Creasy’s rage. It’s a visual manifestation of a man who has lost his anchor and is now operating on pure, efficient instinct.

Lighting Style

The lighting is a beautiful contradiction: naturalistic but highly expressive. Cameron uses the Mexico City sun as a blunt instrument. We see a lot of side-lighting and high-contrast setups. In the early scenes with Lupita, there’s a softness a bit of “warm bloom” creeping in that reflects the humanity she’s bringing back to his life.

But once the revenge kicks in, we move into heavy chiaroscuro. Deep shadows swallow half of Denzel’s face, leaving only a glint in his eye. They used practicals neon signs, car headlights, street lamps to create pockets of intense color. It gives the city a “lived-in” glow that feels both dangerous and poetic.

Compositional Choices

Compositionally, the film is “right-heavy” and often uses slightly off-kilter, canted angles to keep the audience uneasy. Early on, Creasy is often dwarfed by empty space, emphasizing his isolation. As he and Lupita bond, the framing tightens up into intimate two-shots at eye level.

During the “Artist of Death” sequences, the compositions become claustrophobic. Cameron uses a lot of “visual clutter” shooting through grates, fences, or car windows to create depth cues that make you feel like a voyeur. It’s less about “pretty pictures” and more about purposeful, impactful visual communication.

Lensing and Blocking

The lensing strategy is brilliant. They used Long Lenses (telephotos) for surveillance-style shots, giving you that sense that someone is always watching. Then they’d flip to wide-angle lenses in the middle of a crowded street to make it feel overwhelming.

The blocking tells the whole story: Creasy starts as a withdrawn, static figure. As the movie progresses, his movement becomes predatory and dominating. He occupies more of the frame, moving with a “predatory grace.” Lupita, by contrast, is often blocked to look small and vulnerable, which ups the stakes for Creasy’s mission. The interplay between their physical presence and Cameron’s kinetic camera is a perfect visual dance.

Man on Fire (2004) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from MAN ON FIRE (2004). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE – FALLOUT (2018) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: BLACK HAWK DOWN (2001) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →