When I sat down to re-watch Ava DuVernay’s 13th, I wasn’t just watching a documentary; I was dissecting a visual argument. I wanted to see how the lens choices, the lighting, and the final look in the suite worked together to make a historical thesis feel like an urgent, visceral punch to the gut.

13th isn’t a passive history lesson. It’s a meticulously built engine. It tracks the lineage of mass incarceration back to that single, devastating loophole in the 13th Amendment. A lot of reviewers talk about the facts, and they’re right the history is fascinating and terrifying. But for me, the power of this film is in its execution. It takes what could have been a dry, academic “talking heads” piece and turns it into a high-end cinematic experience that refuses to let you look away.

About the Cinematographer

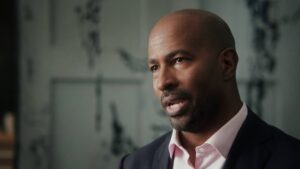

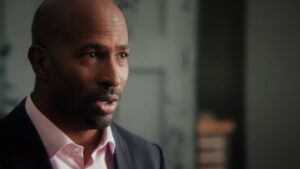

The visual soul of 13th comes from Hans Charles and Kira Kelly. Their collaboration is seamless. They had to juggle a mess of formats shaky cell phone clips, grainy archival reels, and polished new interviews and somehow make it all feel like it belonged in the same world.

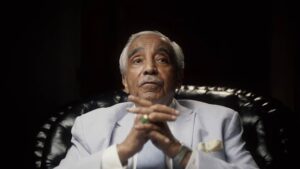

The lighting, in particular, is magnificent. It’s not just “good for a documentary.” It’s sculptural. They understood that light can give a face gravitas and weight. Their work, under DuVernay’s direction, never feels like it’s showing off. It has a quiet authority. As one critic noted, the “milieu” of these subjects makes every interview feel intimate and vital. That’s a massive feat in a genre where you’re often fighting uncontrolled environments and bad locations. Charles and Kelly didn’t just document these people; they gave them a stage.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, this is where I live. Paul Yacono handled the grade here, and he did something brilliant: he leaned into a controlled, “heavy” naturalism. There’s a specific desaturation throughout the film that feels grounded and serious. It’s not “stylized” in a way that feels fake; it’s stylized in a way that feels like truth.

Take the shot around the 03:19 mark the cotton field. It’s desaturated, almost monochromatic, shot in soft, overcast daylight. It doesn’t look like a postcard; it looks like a memory that’s been stripped of its life. That’s the power of a good grade.

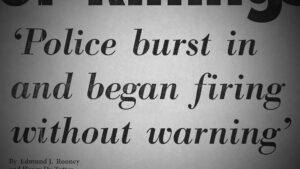

The real challenge, though, was the archival integration. You’re dealing with newsreels, Birth of a Nation clips, and dashcam footage all with different gammas, noise profiles, and color spaces. Yacono kept the skin tones in the contemporary interviews rich and accurate (crucial for a film about race) while using the grade to bridge the gap between the past and present. The shadows have a lot of density without being totally “crushed,” and the highlight roll-off is smooth, giving it a filmic quality that keeps the digital footage from feeling “plastic.”

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

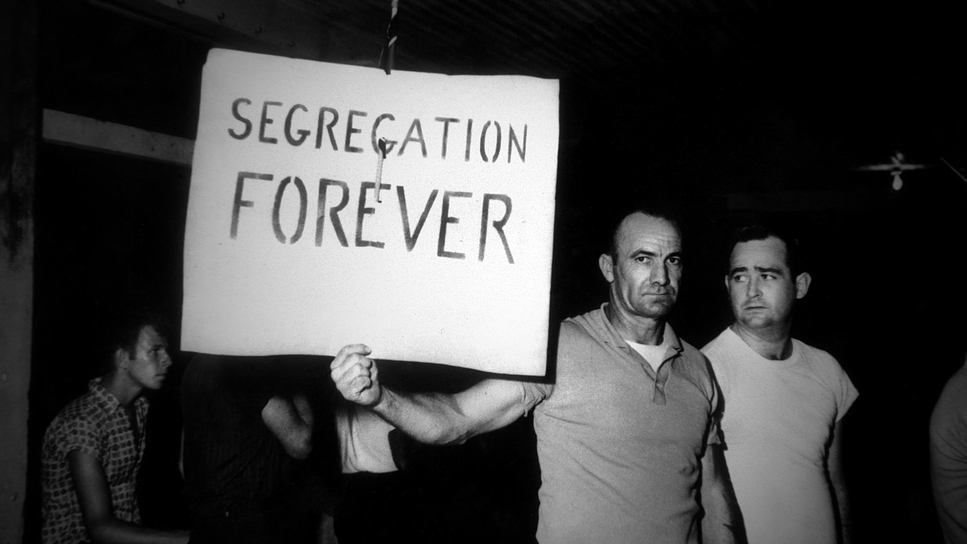

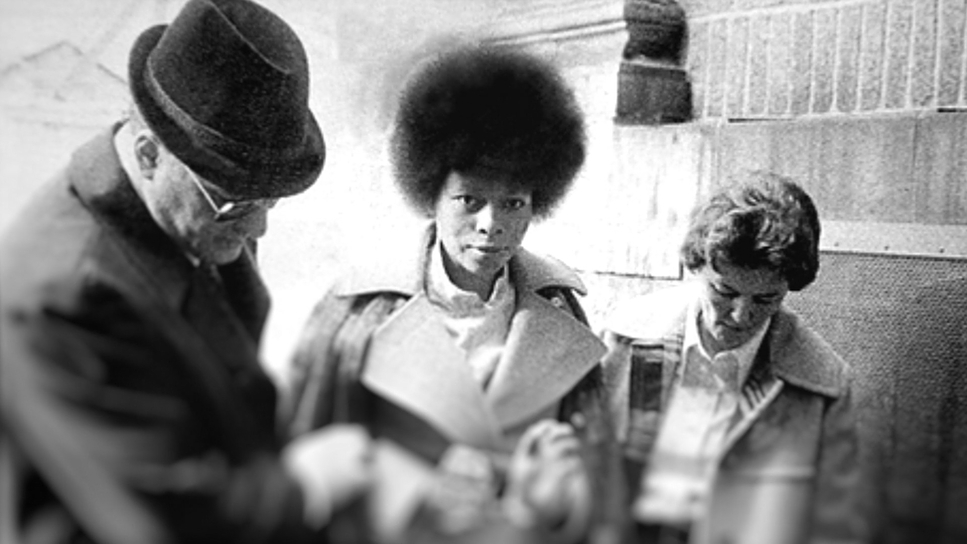

The visual strategy here is a direct reflection of the film’s thesis: that slavery didn’t end; it just morphed. This idea of a persistent, evolving shadow required a visual language that could bridge a hundred years of media.

DuVernay’s vision required a sense of “relentless immediacy.” To make the audience feel the history, the cinematography couldn’t be detached or academic. It had to be “jarring.” By putting high-end, beautifully lit interviews right next to raw, handheld cell phone footage of police brutality, the film creates a dialogue. It’s forcing the past and the present to fight it out in the same frame. The visual language acts as an interrogator, making the “facts” feel emotional rather than just informative.

Lensing and Blocking

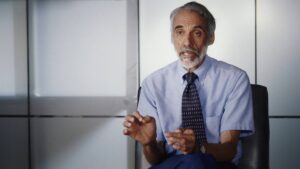

The lens choices for the interviews were clearly deliberate. They stayed mostly in the 50mm to 85mm range the “sweet spot” for human portraits. These lenses provide a naturalistic compression that isn’t as cold as a wide lens or as flat as a long telephoto.

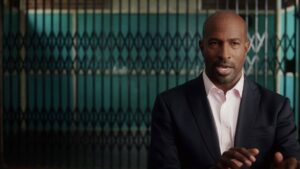

In a doc, “blocking” is really about the environment. The “varied milieu” we see isn’t accidental. Whether it’s a library or a correctional facility, the subjects are positioned to feel part of a world, yet isolated enough to demand our attention. The shallow depth of field isn’t just an aesthetic “pro” look; it’s a tool for focus. It tells the viewer: “The world outside is noisy, but right now, this person’s testimony is the only thing that matters.”

Compositional Choices

The compositions in 13th are all about credibility. For heavy hitters like Angela Davis or Newt Gingrich, the framing is direct and eye-level. No “Dutch angles” or weird perspectives just a balanced, medium-close-up that forces an intimate connection.

I love how they used depth. The backgrounds are meticulously chosen to inform us about the speaker’s world without being a distraction. Using a medium telephoto to slightly compress the background removes the “visual clutter” of the room. It creates a sense of intimacy that transcends the screen. When the film shifts to archival footage, the compositions change to match the era wider, more formal, or inherently chaotic serving as visual markers that tell us exactly where we are on the timeline.

Camera Movements

In this film, the camera knows when to shut up. For the interviews, it’s mostly static. That stillness isn’t passive; it’s a choice to convey authority. It gives the expert testimonies a sense of weight.

But when the film needs to show the systemic scale of the issue, the movement kicks in. We get sweeping aerials and slow, deliberate dollies. The real “movement,” though, happens in the editing. The “cross-cuts” between Trump rallies and historical protests create a frenetic, handheld energy. It’s a brilliant contrast: the dignified, static interviews vs. the chaotic, moving “power of the cell phone.” This interplay is the film’s cinematic engine.

Lighting Style

I’ve heard people call the lighting in 13th “magnificent,” and they aren’t exaggerating. Charles and Kelly avoided the trap of flat, “safe” documentary lighting. Instead, they went for mood. They used soft, diffused key lights, usually off-axis, to sculpt the subjects’ faces.

The lighting feels “motivated” like it’s coming from a window or a lamp in the room even though we know there are professional units just out of frame. The rim and hair lights are subtle. They provide just enough separation to keep the subject from disappearing into the shadows. The result is a look of quiet dignity and introspection. It respects the subject, allowing them to speak their truth in a space that feels both intimate and thoughtfully constructed.

Technical Aspects & Tools

13th — Technical Specifications

| Genre | Documentary, Political, History, Drama |

| Director | Ava DuVernay |

| Cinematographer | Kira Kelly, Hans Charles |

| Production Designer | Leanne Dare |

| Editor | Spencer Averick |

| Colorist | Paul Yacono |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78 – Spherical |

| Format | Digital |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Overcast |

| Story Location | North America > United States of America |

| Filming Location | North America > United States of America |

Shot in 2016, 13th almost certainly utilized the high dynamic range of the ARRI or RED families. To get those skin tones and that shadow detail, you need a sensor that can handle a lot of latitude.

But the technical achievement isn’t just the camera package; it’s the post-production workflow. Stitched together from 1915’s Birth of a Nation, dashcams, and 4K digital interviews, the film is a technical tapestry. The team had to upscale, clean, and color-match a visual “cacophony” into a single, coherent experience. Using tools like DaVinci Resolve, they managed to harmonize these disparate sources without losing the raw, “real-world” texture of the archival clips.

13th (2016) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from 13th (2016). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: THEY SHALL NOT GROW OLD (2018) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE GRAND ILLUSION (1937) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →