Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 masterpiece, The Red Shoes, isn’t just a film to me. It’s a foundational text. As a colorist and filmmaker, I look at this work as a searing exploration of the very thing that drives us: that intoxicating, often destructive, allure of creation.

I first saw The Red Shoes in my early twenties. If I’m honest? It didn’t click. But after years spent in dark rooms staring at scopes and agonizing over skin tones, revisiting it felt like a religious experience. It’s a story about art demanding everything and the visual storytelling is a testament to that demand.

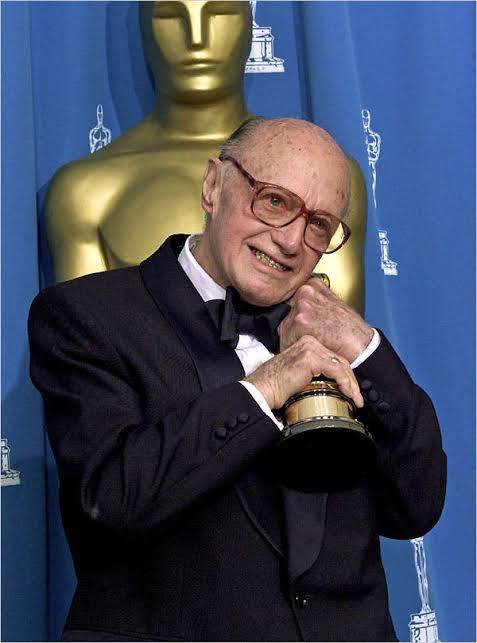

About the Cinematographer

At the heart of this visual splendor is Jack Cardiff. People call him a visionary, but that feels like an understatement. Along with Powell and Pressburger The Archers Cardiff set a standard for expressive filmmaking that we’re still trying to catch up to.

When you watch Cardiff’s work, there’s a tactile, almost sensual quality to the image. It’s not just “pretty.” It’s painterly. It’s as if Monet and Renoir traded their brushes for a Technicolor Three-Strip camera. Cardiff wasn’t just capturing light; he was sculpting it to create an ethereal, dreamlike fantasy. He pushed the boundaries of Technicolor, a process that could easily turn garish, and instead made it sing with nuance. For those of us in the industry, his work on The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus remains the ultimate North Star.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The creative engine here wasn’t a technical brief it was a philosophy. The Archers and Cardiff approached the frame with the sensibility of classical painters. They wanted to evoke feeling through the sheer force of light and color.

Because the film is a meta-narrative about art itself ballet, music, painting the creators were acutely aware of their own artistic drive. They recognized that the same “compelling device” that drives Vicki and Lermontov also drove them. This commitment to the craft is exactly why Martin Scorsese famously poured his own resources into its restoration. He didn’t just see a movie; he saw a declaration of intent. It’s a vibrant reminder that cinema, like ballet, can be an act of pure, unadulterated art.

Lighting Style

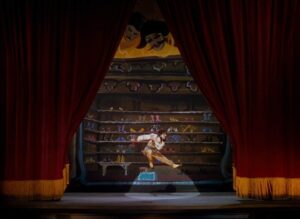

Cardiff’s lighting is a masterclass in Technicolor expressionism. What fascinates me is the deliberate contrast between the “real world” and the “stage world.” In the backstage scenes, the palette is surprisingly muted almost desaturated and drab. It emphasizes the routine, the sweat, and the “minutiae” of the grind.

But once we hit the stage? The lighting shifts into a different dimension. The colors burst. It’s high-key, vibrant, and unapologetically theatrical. Then, Cardiff flips the script again during the “Red Shoes” ballet, utilizing heavy chiaroscuro and expressionistic shadows. The stage becomes a nightmarish landscape reflecting Vicki’s internal fracture. As a colorist, I’m floored by the shadow detail in these dark interiors. Even in the gloom, there’s texture. Nothing is “crushed” into a muddy black.

Lensing and Blocking

The lensing and blocking here are a ballet of their own. Cardiff and The Archers understood that the camera needed to move with the same precision as the dancers.

While specific lens data from 1948 is a bit like chasing ghosts, the visual intent is clear. Wide glass was used to capture the sheer scale of the Mercury Theatre, making the “set pieces” feel massive and immersive. In the dramatic beats, the camera pushes in, likely on longer focal lengths, to catch the subtle shift in Lermontov’s “sad eyes” or Vicki’s mounting panic.

The blocking is even more sophisticated. Look at how Vicki is often positioned in a literal triangle between Lermontov and Julian. Her physical placement mirrors her psychological tug-of-war. Every movement is choreographed for the lens, creating lines that guide the eye exactly where Cardiff wants it.

Camera Movements

In 1948, camera movement wasn’t about “gimbal-smooth” perfection; it was about theatrical intent. We’re talking about massive, heavy Technicolor rigs on dollies and cranes. Achieving fluidity with that much iron is a miracle of engineering.

The Mercury Theatre performance features a spinning camera shot and a snap close-up on Boris in the audience. It’s aggressive. It pulls you into the energy of the dance and then slams you into Lermontov’s predatory gaze. During the 15-minute ballet, the camera doesn’t just watch it dances. It swirls and jolts, mirroring Vicki’s descent. The mirror transition is a stroke of genius a low-tech, high-concept way to bridge two realities without a word of dialogue.

Compositional Choices

Cardiff masterfully utilized the 1.37:1 aspect ratio. Today, we’re used to widescreen, but this nearly square frame allows for incredible verticality and depth.

In the grand ballet sequences, Cardiff uses deep staging. You aren’t just looking at the lead; you’re seeing the entire corps de ballet in a rich tapestry of movement. Even in these wide tableaux, Vicki remains the anchor, often framed by architectural elements that keep our focus locked on her emotional journey. It’s a constant interplay: wide theatrical grandeur versus intimate, tight psychological close-ups. It reinforces the film’s core conflict the glorious art vs. the grueling reality behind the curtain.

Color Grading Approach

This is where my world truly intersects with the film. To talk about The Red Shoes is to talk about the Technicolor heritage and the immaculate 2010 restoration.

From a colorist’s perspective, the 4K Ultra HD release (with Dolby Vision) is a revelation. It’s not just about cranking the saturation. It’s about intelligent hue separation. That iconic red has to pop with intense vibrancy without bleeding into the skin tones or the cooler blues of the set. The “tonal sculpting” here is exemplary. The skin tones remain naturally warm and grounded, providing a sense of realism even when the environment goes full fantasy.

The highlight roll-off is what really gets me. In the bright stage lights, the whites don’t just clip into sterile digital holes; they retain a softness, a filmic texture. The black levels are handled with a gentle hand preserving dimensionality rather than obliterating it. It doesn’t feel like a modern “digital” grade; it feels like a careful polish of Cardiff’s original vision.

Technical Aspects & Tools

The Red Shoes (1948) | 1.37:1 | Technicolor Three Strip

| Genre | Drama, Fairytale, Fantasy, Dance, Music, Romance |

| Director | Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger |

| Cinematographer | Jack Cardiff |

| Production Designer | Hein Heckroth |

| Costume Designer | Hein Heckroth |

| Editor | Reginald Mills |

| Time Period | 1940s |

| Color | Warm, Desaturated |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 |

| Lighting | Soft light |

| Lighting Type | Artificial light |

| Story Location | England > London |

| Filming Location | England > London |

| Camera | Technicolor Three Strip Camera |

We have to appreciate the foundational tech that makes this film endure. The preservation of the 1.37:1 ratio is vital it grounds the film in its era while proving how much power you can pack into a square frame.

The 2010 4K restoration was a monumental task. Scanning those original Technicolor negatives recovered detail we haven’t seen in decades. You can see the actual texture of the makeup and the subtle “nuances” in the facial features that were lost on older transfers.

Adding HDR10 and Dolby Vision wasn’t just a marketing gimmick. It expanded the color volume. We’re seeing a range of luminance that finally does justice to the Three-Strip process. And thank God they kept the film grain. It’s modest, organic, and adds that “cinematic feel” that no amount of CGI can replicate. This is a film that relies on lighting, set design, and traditional editing to create a “beautiful piece of artwork.”

The Red Shoes (1948) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from The Red Shoes (1948). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: THE ACT OF KILLING (2012) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: WHAT IS A WOMAN? (2022) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →