I want to dig into Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’s 2014 documentary. This isn’t just a film; it’s a historical artifact. Mark Kermode called it “the most chilling thriller of the year,” and he wasn’t exaggerating. It turns a confined hotel room into a pressure cooker, proving that sometimes, extreme restraint is the most violent form of drama.

About the Cinematographer

The most striking thing about Citizenfour is that the “architect” was the director herself. Laura Poitras didn’t just call the shots; she was the operator. We’re so used to films having a separate DP brought in to “craft” a look, but here, the aesthetic is born entirely from the act of documenting a clandestine meeting in real-time. Kirsten Johnson and Katy Scoggin helped with the footage outside the Hong Kong hotel, but Poitras’s hand defines the core of the film.

Because she was the one holding the camera, the lens stops being an “objective observer” and starts feeling like a participant. You can feel her own anxiety and journalistic urgency in the frame. There was no room for a crew or elaborate setups. The camera had to be invisible. This direct authorship creates a singular, unbroken vision where the act of filming is just as important as the whistleblowing itself.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

The inspiration here is pure paranoia. The visual choices are dictated by the overwhelming sense that everything every phone, every light fixture is a potential bug. It’s not just “movie paranoia”; it’s a psychological state that the cinematography builds brick by brick.

The hotel room in Hong Kong isn’t just a location it’s a crucible. Poitras didn’t need grand cinematic gestures. Instead, she focused on the weight of small things: a shared glance, the tap of a keyboard, the hum of the air conditioning. The inspiration wasn’t about “grandeur.” It was about claustrophobic intimacy. It pulls the audience into that precarious space with Snowden, making us feel the “unlimited reach” of the surveillance state. It’s a masterclass in letting the raw truth speak louder than the camera.

Camera Movements

There’s a huge misconception that Citizenfour is just “shaky handheld documentary footage.” It’s actually the opposite. As Thomas Flight noted when comparing it to Oliver Stone’s Snowden, most of the footage in this documentary is remarkably steady.

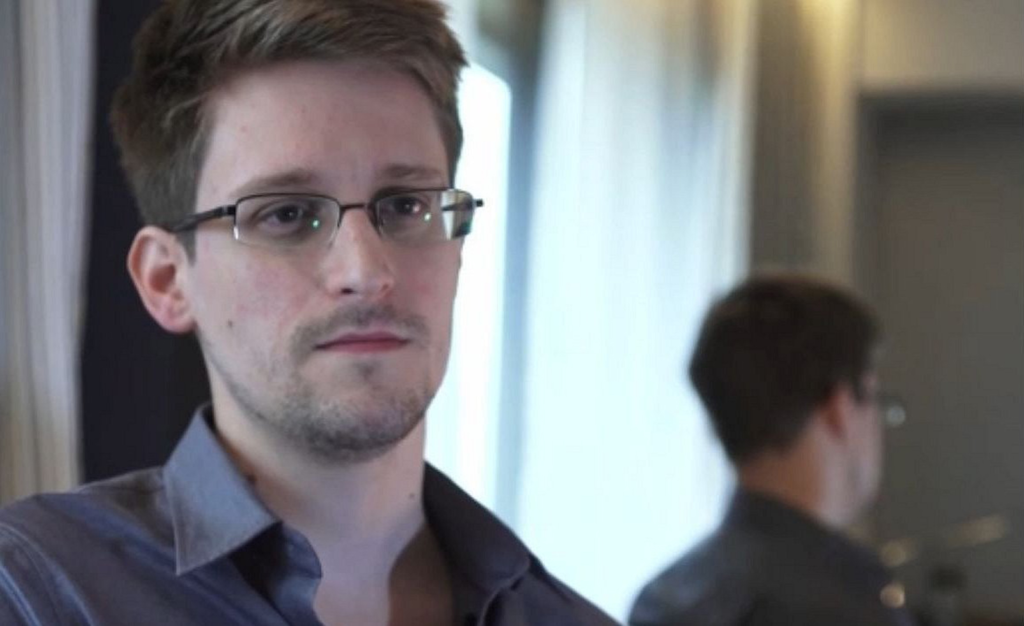

That steadiness isn’t an accident. It’s a calculated choice. Handheld creates urgency, sure, but too much of it is just distracting. By keeping the camera still, Poitras forces us to focus on Snowden’s face his calm, his precision, his vulnerability. It feels like the camera is holding its breath. When the camera does move, it’s motivated. A slight push-in or a gentle breath of handheld during the fire alarm incident feels like a jolt because the rest of the film is so anchored. It’s a brilliant use of contrast.

Compositional Choices

The compositions in Citizenfour are incredibly economical. Poitras relies heavily on static, medium close-ups, often framing subjects slightly off-center. It creates this subtle, persistent sense of unease. You also see a lot of negative space not for “art’s sake,” but to represent the vast, unseen forces of the state lurking just outside the frame.

Windows are a recurring motif. They show the dense Hong Kong skyline, but they’re usually blurry and out of focus. It emphasizes Snowden’s isolation. He’s in this tiny room, but he’s about to shake the entire world outside that window. Then you have the laptop. often the only thing lighting his face. These tight frames on hands typing or documents being read create a visual claustrophobia that makes the act of information transfer feel incredibly dangerous.

Lighting Style

This is a masterclass in motivated realism. There are no gels, no theatrical shadows, and no “Hollywood” setups. Poitras relies almost entirely on the practical light sources available in the room.

Most of the light comes from the large window, shifting organically with the time of day. But the real “key light” in this movie is the laptop screen. It provides this soft, bluish luminescence that hits Snowden from below. It’s not “pretty” in a traditional sense it’s eerie and digital. It grounds the film in the reality of the situation. From a technical standpoint, the dynamic range is handled beautifully; they didn’t push for high-contrast drama. Instead, they preserved the details in the shadows and the highlights of the window to keep it looking believable and raw.

Lensing and Blocking

In a high-stakes environment like this, you need gear that’s versatile but discreet. Poitras likely leaned on neutral prime lenses probably in the 35mm to 50mm range. These focal lengths mimic human vision, which is why the footage feels so immersive and “honest.”

The “blocking” isn’t choreographed; it’s captured. When Snowden leans into his laptop or pulls the “mantle of power” (that white towel) over his head to hide his password, it’s not a cinematic contrivance. It’s a survival tactic. The camera just happens to be there to frame it. The shallow depth of field isolates him, making him the undeniable focal point of a global storm. The lens observes rather than directs, turning spontaneous behavior into a profound visual metaphor for vulnerability.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, this is where I really get analytical. The grade in Citizenfour is incredibly understated, but it’s doing a lot of the heavy lifting. It isn’t “stylized,” but it is meticulously crafted to feel chilling.

The palette leans into cool, desaturated tones lots of muted blues, greys, and greens. It creates a somber, intellectual atmosphere. As a pro, I notice the lack of vibrant, distracting colors; they wanted your eyes on the human emotion, not the wallpaper. We also see a very controlled contrast. It avoids those harsh, “video-ish” blacks and blown-out whites. The highlight roll-off is smooth, which is impressive given the digital sensors of 2013-2014. It has a “film print” sensibility that makes the digital capture feel weightier. It’s a quiet grade, but it speaks volumes about the gravity of the story.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Discretion was the priority here. While they haven’t shouted about the gear list, you can tell they needed portability and low-light performance. They likely used compact digital cinema cameras or high-end DSLRs that were the standard back then think Canon C300 or maybe even a 5D Mark III. These allowed for that cinematic depth of field without looking like a “film production” was happening in the lobby.

The audio is just as critical. Without clean sound, the technical details Snowden reveals would be lost. You can hear every click of the keyboard and every muffled ambient noise. The technical approach wasn’t about having the flashiest gear; it was about using reliable, “invisible” tools to capture a sensitive story with maximum fidelity and zero intrusion.

- Also read: THE TALE OF THE PRINCESS KAGUYA (2013) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: WALTZ WITH BASHIR (2008) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →