Today, I’m diving into a film that is practically etched into the DNA of cinema history one I find myself returning to whenever I need a reminder of why I do what I do. It’s Federico Fellini’s 1954 masterpiece, La Strada. La Strada is a special case. It’s raw. It’s human. Yet, it has this weird, almost ghostly “Fellini magic” that shouldn’t work with its gritty neorealist roots, but somehow does. Let’s pull back the curtain on the cinematography that makes this journey so unforgettable.

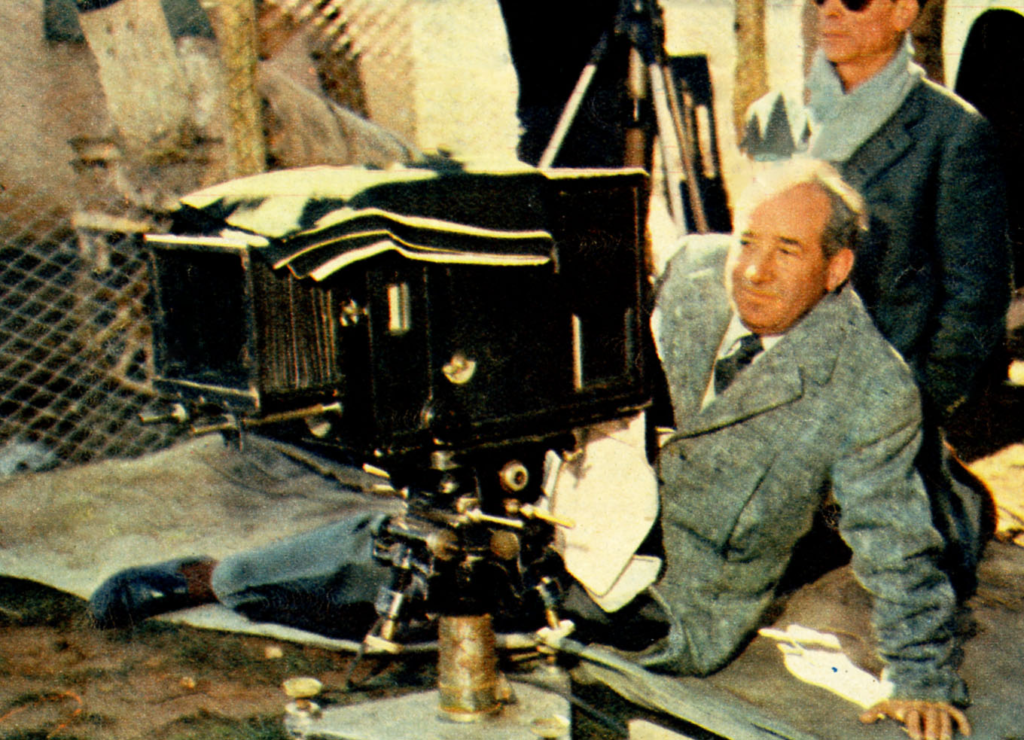

About the Cinematographer

The man behind the lens was Otello Martelli. He’s a name you need to know if you care about the evolution of Italian style. Martelli was a long-time Fellini collaborator (I Vitelloni, Variety Lights), and you can really feel that shorthand on screen.

What’s fascinating here is how Martelli straddles two eras. He’s working in the tradition of Italian neorealism real locations, available light, a certain documentary “dirt” but he’s starting to sculpt the image. Martin Scorsese once noted that while this film comes out of neorealism, the camera work is “more controlled” and the lighting is “more sophisticated.” It’s true. This isn’t the run-and-gun feel of Rossellini. Under Fellini’s eye, Martelli was beginning to move toward the operatic, theatrical visions of 8½. It’s a transition period captured on 35mm, and it’s beautiful to watch.

Color Grading Approach (The Colorist’s Perspective)

Since this is my wheelhouse, let’s talk about the “color” of a black-and-white film. To me, B&W is just a deeply sophisticated form of monochromatic grading. When I look at La Strada, I’m not just seeing “gray” I’m seeing tonal sculpting.

If I were grading a restoration of this today, my primary goal would be preserving that specific 1950s print-film density. The shadow detail in the night scenes is incredible; it’s dark, but never “muddy.” Look at the highlight roll-off on Gelsomina’s face it has a creamy, organic quality that modern digital sensors still struggle to replicate. There’s a richness in the mid-tones that shifts depending on the mood. In the bleak winter sequences, the contrast feels flatter, heavier, almost oppressive. Then you get to the farmhouse scene with the child, and suddenly the luminance values are pushed; the whites bloom just enough to give Gelsomina a subtle, angelic halo. It’s not just a technical choice. It’s an emotional one.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Fellini didn’t start with a storyboard; he started with “vague feelings of melancholy and a shadow of guilt.” He had these mental snapshots: snow falling silently on the sea, cloud compositions, a singing nightingale. That’s the magic of this film it’s abstract emotion translated into concrete visuals.

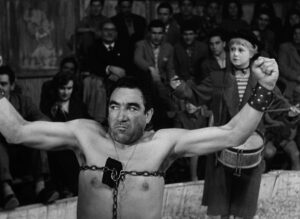

The characters themselves are elemental. Zampano is Earth. Gelsomina is Water. El Matto is Air. You see this in how they are captured. Zampano is always grounded, heavy, and solid in the frame. Gelsomina is fluid and erratic. Even the accidents of production fed the look. Anthony Quinn was pulling double duty shooting Attila in the afternoons, leaving him exhausted for La Strada’s early morning calls. That “haggard look” wasn’t makeup it was real fatigue, and Martelli captured that raw weariness perfectly.

Camera Movements

In La Strada, the camera isn’t just an observer; it’s an empathetic witness. As Scorsese pointed out, the movements are controlled. We don’t get a lot of wild, handheld chaos. Instead, we get these mournful, deliberate tracks.

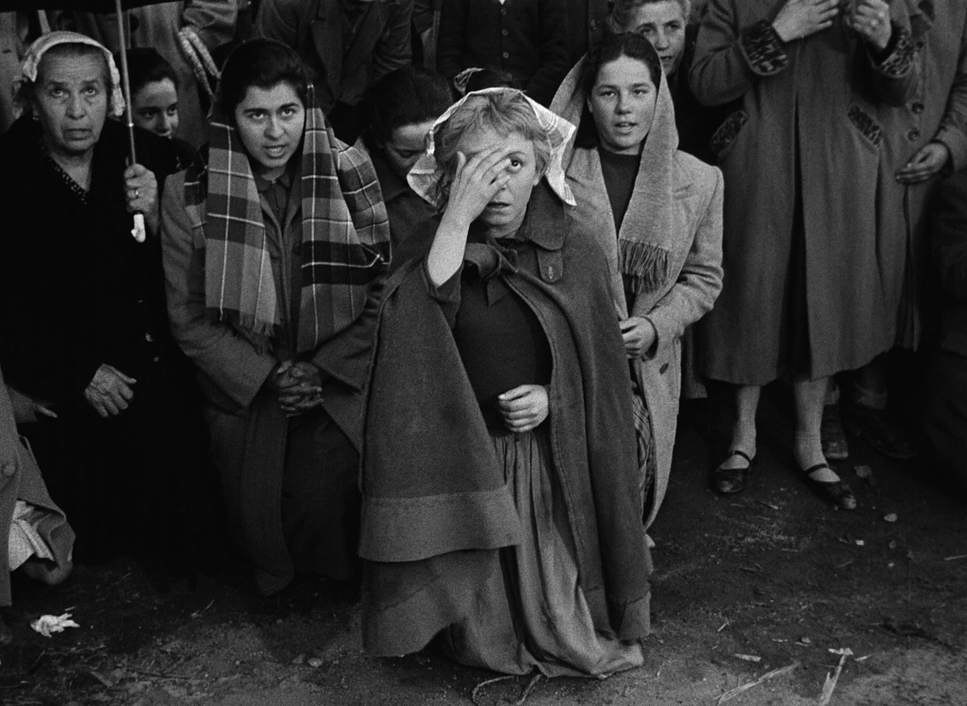

The camera often lingers on Gelsomina. It follows her gaze, mirroring her wonder or her crushing loneliness. Think of the shots where she’s walking alone against a vast, indifferent landscape. These aren’t just static frames; there’s often a very slow, almost imperceptible push-in. It draws us into her internal state without feeling like the film is “poking” us. It’s quiet. It doesn’t beg for your attention; it just waits for her to break your heart.

Compositional Choices

Composition here is a masterclass in using “negative space” to show how small these people are in a harsh world. Fellini and Martelli use deep space constantly, placing characters in environments that absolutely dwarf them.

The “triangle of conflict” between our three leads is literally built into the frames. When they’re together, the balance is always “off.” Zampano usually takes up the lower, heavier part of the frame the Earth. El Matto often appears in the upper registers or flits in and out of the edges the Air. One of my favorite shots is Gelsomina at the farmhouse seeing the disabled child. It’s a tableau. It feels like a painting. It’s not “realistic” in a documentary sense, but it’s deeply “true” in a poetic sense.

Lighting Style

This is where we enter “Fellini Magic Land.” While the film uses natural environments, the lighting is anything but “accidental.” Scorsese called it “sophisticated,” and he was right.

I’m obsessed with the “bleak early light” Fellini insisted on for the morning shoots. It’s high-contrast, raking light that defines every texture of the stone walls and the grit on the actors’ skin. In the interiors, Martelli uses candles and bare bulbs, but he controls them with such precision. It’s tonal sculpting at its finest using light to create separation and emotional weight. There’s a sense of melancholic wonder in every highlight.

Lensing and Blocking

For La Strada, Martelli favored lenses that feel close to the human eye. No extreme wide-angle distortion, no heavy telephoto compression. It’s an empathetic perspective. He uses a controlled depth of field to keep the characters sharp while the world behind them stays just recognizable enough to feel real, but soft enough to keep our focus on the performance.

The blocking is where the character dynamics really live. Zampano moves with a heavy, purposeful stride; he dominates the space. Gelsomina moves in smaller, hesitant patterns. She often looks constricted, even when she’s outdoors. When the Fool (El Matto) enters, he cuts across their paths, disrupting the visual flow. It’s theatrical staging, but it’s done with such cinematic grace that it never feels “staged.”

Technical Aspects & Tools

| Genre | Drama, Road Trip, Comedy, Romance, Melodrama |

| Director | Federico Fellini |

| Cinematographer | Otello Martelli, Carlo Carlini |

| Production Designer | Mario Ravasco |

| Costume Designer | Margherita Marinari |

| Editor | Leo Catozzo |

| Time Period | 1950s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light, Top light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | Europe > Italy |

| Filming Location | Lazio > Fiumicino |

The production was a nightmare, honestly. They shot in February with temperatures hitting -5°C. No heat, no hot water. The cast slept in their clothes. You can’t “act” that kind of cold; it’s just there, in the grain of the film.

Technically, the “Italian style” of the time shooting without live sound gave Fellini a weird kind of freedom. He’d play music on set to get the actors in the right mood and have them count numbers instead of saying lines. As someone who usually has to worry about sync-sound constraints, I find that liberating. They even “faked” snow by piling bags of plaster onto bedsheets. It’s grassroots filmmaking at its most improvisational, and that grit is exactly why the film feels so authentic.

La Strada (1954) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from LA STRADA (1954). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

- Also read: G.O.R.A. (2004) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: RIO BRAVO (1959) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →