Shoplifters (2018), Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Palme d’Or winner. When a film like Shoplifters comes along, I’m not just looking at a beautiful narrative; I’m looking at a masterclass in how visual decisions from the specific glass on the camera to the density of the shadows in the grade. culminate in an experience that feels raw and lived-in.

Kore-eda is a director who, as Mark Kermode puts it, wants “cinema to be cinematic.” He’s not interested in radio plays with pictures. He wants the image to do the heavy lifting. Shoplifters is the ultimate proof of that. It invites us into the lives of an unconventional family on the fringes of Tokyo, where bonds are forged by shared survival rather than blood. For me, dissecting this cinematography isn’t an academic exercise; it’s a deep dive into the craft that makes a story like this actually hurt when you watch it.

About the Cinematographer

The understated brilliance of these visuals rests on Ryūto Kondō. He and Kore-eda have this shorthand that results in an observational style that is almost eerily natural. People often say Kore-eda isn’t a “showy” director, but that’s a bit of a backhanded compliment. It takes an incredible amount of ego-suppression for a DP like Kondō to make a camera feel this invisible.

Kondō’s camera always seems to be in the right place, but it never feels like a “statement.” It’s intentional. He’s giving the characters room to breathe without the burden of overt stylistic flourishes. It’s less about “composing a shot” and more about dissolving the presence of the lens entirely, making the frame feel like a window you just happened to look through.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

Kore-eda started with stories of “domestic crimes” pension fraud, shoplifting, the small ways people survive when society ignores them. He was fascinated by the public anger directed at these minor infractions compared to the massive, systemic failures of the world. This moral “gray area” is the bedrock of the film’s look.

How do you visually frame a family that is simultaneously loving and, by legal definition, a group of kidnappers and thieves? You do it through non-judgmental naturalism. The inspiration here wasn’t to make a moral point, but to create a “shambolic, but apparently loving” environment. The camera becomes a compassionate observer for people pushed to the margins. It’s about the “small moments,” and the cinematography is crafted to highlight physical gestures a hand on a shoulder, the way they share a meal rather than relying on dialogue to explain the emotion.

Lensing and Blocking

Looking at the technical specs, the choice of glass is what gives this film its soul. They used a mix of Canon K35s and Zeiss Ultra Primes. As a colorist, I love the K35s they have this vintage, slightly lower-contrast feel and a beautiful flare that keeps the image from feeling too “digital” or clinical.

The blocking in those cramped rooms is nothing short of masterly. You have an ensemble cast living in two rooms, yet it never feels like a stage play. They are constantly overlapping, sharing frames, and physically leaning on one another. When they shoplift, the blocking shifts into a precise, choreographed dance that “finger rolling” gesture isn’t just a plot point; it’s a visual rhythm. It’s about using the actors’ bodies to tell the story of their unity.

Lighting Style

The lighting in Shoplifters is all about “motivated” sources, and it’s remarkably disciplined. Most of the light feels like it’s coming from a single bare bulb, a small desk lamp, or the weak sunlight fighting its way through a window.

Indoors, the light is soft but “messy.” It’s not perfectly sculpted; there’s a real grit to it. Shadows aren’t just black they have texture. When Kermode mentions the “underlying darkness,” it’s right there in the fall-off on their faces. They aren’t lit like movie stars; they’re lit like people living in a house with bad wiring and crowded shelves. Even the grocery store scenes use that cold, top-down fluorescent light that feels appropriately sterile compared to the “warm” (if impoverished) lighting of their home.

Compositional Choices

Kondō uses the frame to imply what he doesn’t want to show. Because the family is living in grandma’s tiny house, tight framing is a requirement, but he turns that limitation into a strength.

He frequently frames characters through doorways or windows, using the architecture of poverty to create depth. But the most powerful shot for me is when Yuri is taken back to her parents’ house. We don’t see the abusers. We see a medium shot of the house exterior, the closed door, and the toys outside. It’s devastating because of what it doesn’tshow. We infer the cruelty. That’s pure visual storytelling letting the audience do the work.

Camera Movements

In Shoplifters, movement is a philosophy of restraint. You won’t find any “look at me” crane shots or complex tracking here. It’s all about the subtle pan or a very gentle dolly-in that tightens the frame just enough to catch a change in a character’s eyes.

There’s a deliberate slowness to the pacing. It matches the rhythm of their lives. When the family is together, the camera is usually static, letting us take in the bustling, cramped scene. It feels like watching people on the street unvarnished and raw. This lack of movement makes the moments when the camera does move feel heavy and significant.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Shoplifters: Technical Specifications

Now, let’s correct a common assumption: this wasn’t a digital shoot. Shoplifters was shot on 35mm film (Arricam ST and Arriflex). You can feel it in the latitude. Using 2.8K ArriRaw for the digital intermediate gave them enough room to play, but the “soul” of the image is celluloid.

The use of film stock here is vital. It provides a natural highlight roll-off and a grain structure that digital struggle to emulate perfectly. In the grocery store shots, they likely used the Fujinon Alura Zooms or Angenieux Optimo for flexibility, but the heart of the film is in those wide-aperture primes that capture the Tokyo interior with such intimacy. Using an ACES pipeline in post-production would have been key to keeping that 35mm “look” consistent across every delivery format.

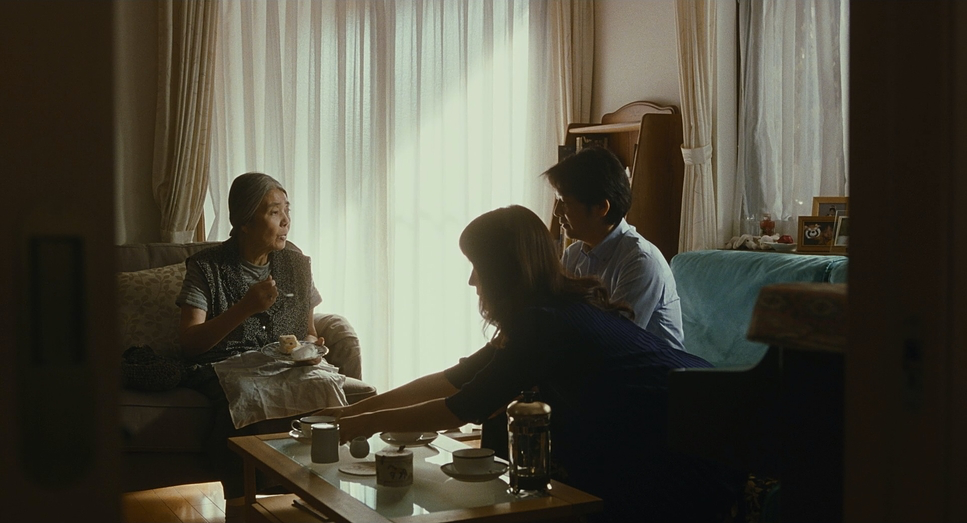

Shoplifters (2018) Film Stills

A curated reference archive of cinematography stills from Shoplifters (2018). Study the lighting, color grading, and composition.

Color Grading Approach

This is where I’d love to get my hands on the RAW files. The actual colorist, Jun Takada, did a phenomenal job of making the grade feel “un-graded.”

If I were sitting at the panel for this, my priority would be tonal sculpting. I’d want the skin tones to feel vibrant and warm a “lived-in” orange/red to contrast with the muted, desaturated greens and blues of the surrounding city. This creates a visual “hug” for the family.

Contrast shaping here is a delicate dance. You want to preserve the shadow detail in those dark corners of the house without making it look “muddy.” You want a painterly quality in the highlights, especially where sunlight hits the dust in the room. I’d lean into a print-film sensibility, adding a slight warmth to the mid-tones and keeping the blacks from ever being “true zero.” It needs to feel like an old, comfortable blanket worn-out, but warm.

- Also read: THE WILD BUNCH (1969) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: THE BIG SLEEP (1946) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →