In an era of “visual noise,” the discipline found in Golden Age cinema is a breath of fresh air. High Noon (1952) remains a towering achievement in this regard. It’s a masterclass in psychological realism disguised as a Western, leveraging every frame to heighten tension and explore the weight of moral choice.

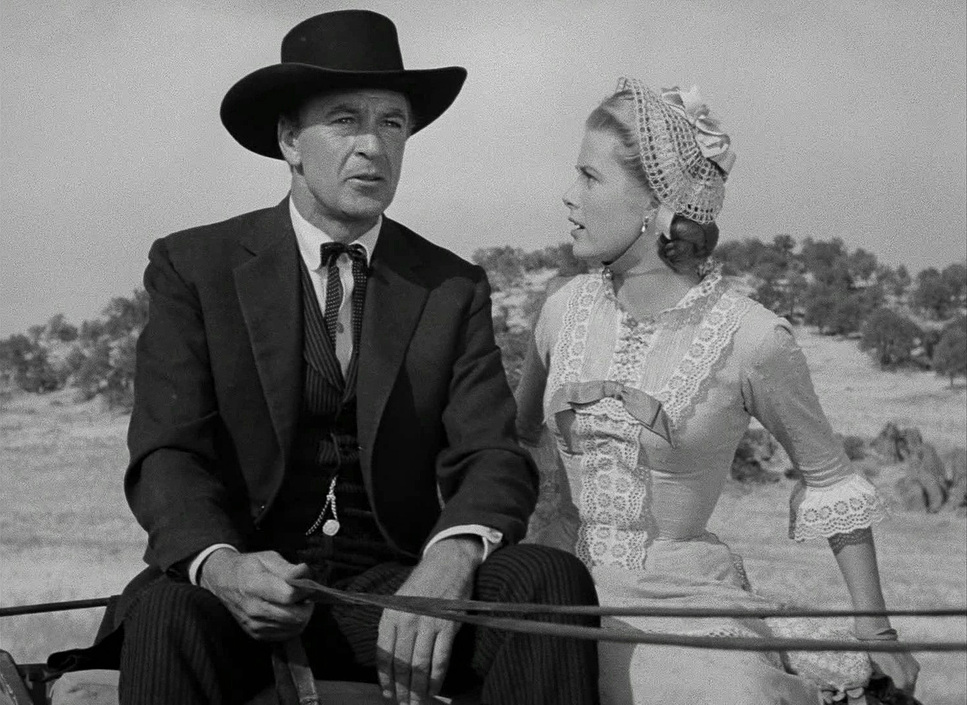

The story is deceptively simple: Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper), newly married and ready to hang up his star, learns that an outlaw he sent away is returning on the noon train to Hadleyville. What follows is a gripping, real-time descent into isolation. My own relationship with this film has evolved from a casual viewing to a deep obsession with its nuanced execution specifically how the visual storytelling works in tandem with a razor-sharp script to depict Kane’s agonizing abandonment.

The Architect of Tension: Floyd Crosby

While Fred Zinnemann’s direction provided the heartbeat, the legendary Floyd Crosby was the eye behind the camera. Crosby was known for a stark, unadorned style that prioritized raw realism over Hollywood “gloss.” In High Noon, his work isn’t about flash. It’s about meticulous observation. He understood that the goal wasn’t to create a spectacle, but to document the psychological toll on Kane. By making the dusty, desolate town of Hadleyville feel suffocating and apathetic, Crosby turned the environment into a character one that is actively closing in on our protagonist.

The Existential Ticking Clock

The core inspiration for the cinematography is the film’s real-time narrative. This isn’t just a gimmick; it’s the guiding principle for every shot. The camera mirrors the internal pressure bearing down on Kane. We constantly cut between Cooper’s increasingly “sweaty” nervousness and the literal clocks marking the seconds. This translates an abstract concept time into a palpable, existential threat. The visuals are designed to make the audience feel that same claustrophobia. It’s a “man against the world” theme boiled down to its essence, using minimalist imagery to amplify the moral stakes.

The Geometry of a Ticking Clock: Camera Movement

The camera movement in High Noon is remarkably understated, which makes the few deliberate moves feel massive. You won’t find sweeping crane shots here; the narrative is about a man trapped, not a man exploring. Instead, Crosby employs slow, agonizing pushes toward Cooper as the mid-day train approaches. These subtle dollies don’t feel like “moves” they feel like the walls of Kane’s world physically contracting. When the camera does pan across the deserted streets, it’s to emphasize the void where help should be. It’s a precise, economical language where every second of screen time is heavy with anticipation.

The 1.37:1 Cage: Compositional Choices

This is where the film’s genius truly shines. Working in the 1.37:1 Academy ratio, Crosby used negative space and depth to visualize abandonment. We see Kane as a tiny figure dwarfed by the empty dirt streets, a compositional choice that reinforces his loneliness without a single word of dialogue. One of the most powerful images is the receding perspective of the train tracks vanishing into the distance a literal vanishing point for Kane’s hope. Deep focus is used to keep the unhelpful townspeople in the frame even when they are in the background, creating a psychological layer where Kane is physically present but emotionally cast out.

The Unforgiving Sun: Lighting Style

As a colorist, I’m fascinated by how Crosby embraced the harsh, high-key light of the American West. It’s “sunny” and “daylight-balanced” in the most brutal sense. The hard light carves out textures the grit on the faces of the outlaws, including a young Lee Van Cleef, and the sweat-filled brows of the terrified townspeople. There’s no soft, “beauty” lighting here. The interiors are equally motivated, using shadows to mirror Kane’s internal darkness. I often look at this film as a study in tonal sculpting; the way light spills through windows to highlight a ticking clock is a perfect example of using naturalism for dramatic punctuation.

The Spatial Geography of Abandonment

The lensing and blocking are instrumental in building the film’s claustrophobic tension. Crosby stayed with standard 35mm spherical lenses, avoiding distortions to keep the perspective grounded and observational. This forces the blocking to do the heavy lifting. When Kane seeks help, he is often blocked in isolation standing alone in the foreground while others cluster in the distance, refusing eye contact. Even the “strong silent type” persona of Gary Cooper is amplified by blocking that positions him as an immovable object against a community that is literally moving away from him. It’s a masterclass in using physical space to define power dynamics.

Sculpting in Monochrome: The Grading Approach

While we don’t “grade” 1952 film in the modern sense, the recent 4K restoration is a masterclass in tonal management. From a professional perspective, “color” in this film is about the purity of the monochrome. The 4K UHD release is a revelation the grayscale is dialed in with incredible precision. The whites are stable without blooming, and the black levels are deep without “crushing” the shadow detail in the textures of the period-accurate costumes. For a colorist, seeing the “finely layered film grain” preserved alongside this level of contrast is the holy grail. It respects the original 35mm print-film sensibilities while using modern dynamic range to let the stark atmosphere truly breathe.

The 35mm Legacy: Technical Execution

High Noon (1952) | Technical Specifications

| Genre | Western, Outlaw, Traditional Western, Epic |

| Director | Fred Zinnemann |

| Cinematographer | Floyd Crosby |

| Production Designer | Rudolph Sternad |

| Costume Designer | Joe King, Ann Peck |

| Editor | Elmo Williams |

| Time Period | 1800s |

| Color | Desaturated, Black and White |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.37 – Spherical |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Hard light |

| Lighting Type | Daylight, Sunny |

| Story Location | New Mexico Territory > Hadleyville |

| Filming Location | Jamestown > Brooks Ranch |

The journey of High Noon from 1952 to a modern 4K Dolby Vision master is a testament to the importance of film preservation. Shot on 35mm film in a 1.37:1 aspect ratio, the restoration from the original camera negative ensures that the clarity is staggering. The move to native 4K resolution reveals details the “grisled” skin, the dirt on the 1800s-style clothing, the depth of the New Mexico-style sets that were simply lost in previous transfers. As a colorist, seeing HDR10 and Dolby Vision applied to a classic like this is exciting; it doesn’t “change” the film, but it allows the original vision of Floyd Crosby to be seen with unprecedented fidelity.

- Also read: A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: TALK TO HER (2002) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →