The film that delivers the ultimate emotional gut punch through sheer visual artistry is Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997). Quentin Tarantino once noted that PTA’s film knowledge “makes me look like an amateur.” He’s right to champion Boogie Nights as a 90s masterpiece. It’s staggering to think Anderson was only 27 hardly “battle-tested” when he delivered something this profound. It isn’t just a story about the adult film industry; as the reviews say, that’s just the “aspirin in the applesauce.” At its core, this is a deeply human story about “family,” tribe, and the desperation to belong. The cinematography doesn’t just capture this; it carries it.

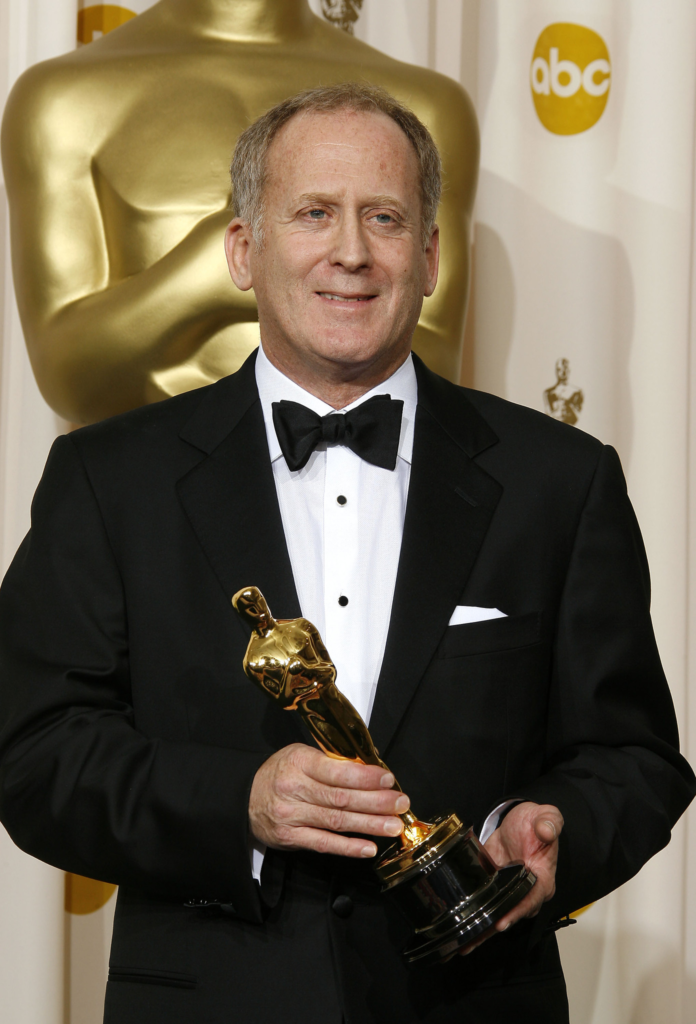

About the Cinematographer

Robert Elswit is the visual architect here. His partnership with PTA on Boogie Nights set the stage for a visual language that would define the director’s entire career. For a young director on his second feature, Elswit’s creative bravery was the “secret sauce.” Even with a modest budget, they didn’t cut corners; they built a world. Elswit didn’t hunt for flashy individual frames. Instead, he used light, movement, and composition to build a cohesive, immersive environment that allowed the characters to actually live inside the frame.

Inspiration Behind the Cinematography

You can feel the ghosts of Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman in every frame. The kinetic energy of Goodfellas and the sprawling, chaotic ensemble work of Altman are baked into the film’s DNA. But Elswit and PTA took those influences and evolved them.

The visual storytelling is tasked with a massive job: mapping the shift from the “hedonistic 70s” to the “sobering 1980s.” This isn’t just a narrative beat; it’s a visual metamorphosis. The cinematography embodies this “rise and fall” the vibrant, saturated excess of the disco era giving way to the fracturing disillusionment of Reaganomics. It’s an active participant in the tragedy, not just a backdrop.

Camera Movements

The camera movement in Boogie Nights is nothing short of bravura. We have to talk about that opening shot a sinuous, continuous take that pulls you into the club, introduces an entire ecosystem of characters, and refuses to let you look away. It’s a bold declaration of intent.

These movements are never just “showing off.” They serve the story. The camera glides with a confidence that mirrors Dirk Diggler’s initial swagger, then shifts into a more observational, disorienting rhythm as the characters’ lives begin to unravel. It’s “operatic” in the way it choreographs actors and space, creating a fluidity that makes the world feel dangerously alive.

Compositional Choices

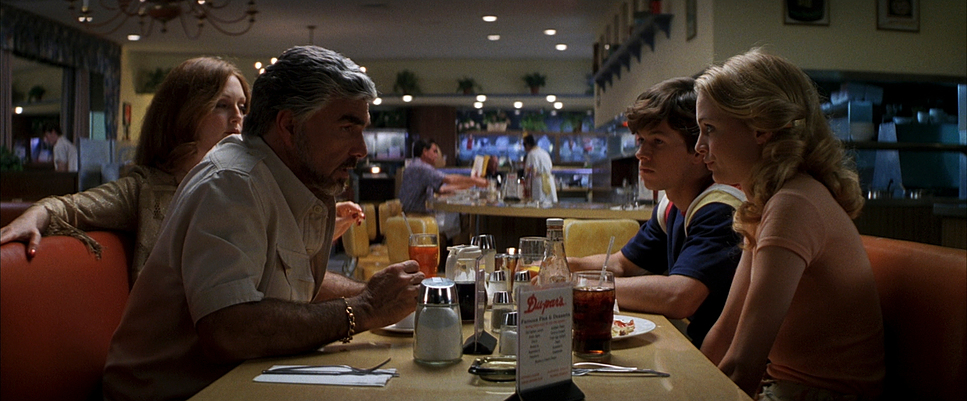

The framing here is incredibly astute. Elswit has a brilliant understanding of how to use wide shots to establish the unity or the rot of the ensemble.

Look at the diner scene with Jack, Amber, Dirk, and Rollergirl. The “empty frame” beside Dirk and Rollergirl is a haunting use of negative space. It highlights the “void” in their lives, signaling their individual brokenness even as they try to play “family.” These are the kind of psychological tools that separate great cinematography from just “pretty pictures.” The frame guides your eye through complex depth cues, forcing you to see the primary action while feeling the weight of everything happening in the background.

Lensing and Blocking

To get that specific 70s texture, Elswit reached for Panavision C-series Anamorphic lenses. This choice is crucial. Anamorphic glass gives you those beautiful, organic flares and that specific “mushed” bokeh that spherical lenses just can’t replicate. It creates a sense of intimacy even in wide-angle shots, pulling the viewer closer into the characters’ orbits.

The blocking is a continuous dance. Characters drift in and out of focus and each other’s lives like a real, fractured family. Dirk’s progression from an awkward kid to a self-proclaimed star and eventually to a man facing reality is underscored by how he is physically positioned and framed within these evolving units. It never feels forced; it feels like destiny.

Lighting Style

The lighting is a masterclass in motivated illumination. Elswit embraces a style that is warm, amber-hued, and heavily reliant on practicals disco balls, neon signs, and period-specific lamps. This isn’t “pretty” lighting; it’s raw realism.

In the first half, the lighting is vibrant, almost pulsating with a “golden hour” glow. This reflects the characters’ optimism. But as the 80s hit, the light turns. It becomes harsher, cooler, and grittier. Shadows deepen, and the once-inviting spaces become foreboding. The lighting doesn’t just illuminate the scene; it tracks the emotional arc of addiction and isolation.

Color Grading Approach

As a colorist, this is where I get really excited. Shooting on Kodak 5248/7248 EXR 100T film stock gave them a foundation of rich reds and saturated oranges that define that nostalgic California look. In the 70s sections, the highlight roll-off is creamy and gentle that classic photochemical beauty we’re always trying to emulate in Resolve today.

When the 80s arrive, the palette shifts. It’s desaturated, flatter, and leaner. But the real genius is the “porn-on-cop-movie” footage Jack Horner is so proud of. Tarantino called it a “flaw,” but I disagree. PTA deliberately made that footage look like trash shot on 16mm, poorly lit, and cheap. It’s a brilliant storytelling device. It visually screams Jack’s delusion and artistic disconnect. We see the lush, anamorphic world of Boogie Nights contrasted against Jack’s mediocre, uninspired reality. That’s not a flaw; it’s tonal sculpting.

Technical Aspects & Tools

Boogie Nights: Technical Specifications

| Genre | Drama, Comedy, Erotic |

| Director | Paul Thomas Anderson |

| Cinematographer | Robert Elswit |

| Production Designer | Bob Ziembicki |

| Costume Designer | Mark Bridges |

| Editor | Dylan Tichenor |

| Colorist | Phil Hetos |

| Time Period | 1970s |

| Color | Warm, Saturated, Red, Pink |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39 – Anamorphic |

| Format | Film – 35mm |

| Lighting | Underlight |

| Lighting Type | Practical light |

| Story Location | California > Los Angeles |

| Filming Location | Los Angeles > Reseda |

| Camera | Panavision Panaflex |

| Lens | Panavision C series |

| Film Stock / Resolution | 5248/7248 EXR 100T |

Shooting on 35mm film with Panavision Panaflex cameras allowed for a dynamic range and grain structure that digital still struggles to match. Given their budget constraints, the crew had to be incredibly disciplined. The intricate tracking shots required a world-class dolly grip and a focus puller who could handle the razor-thin depth of field of those C-series lenses. Every technical decision from the lens choice to the specific film stock was geared toward building a “tapestry” that felt tangible and emotionally resonant.

- Also read: ALMOST FAMOUS (2000) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

- Also read: SERENITY (2005) – CINEMATOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

Browse Our Cinematography Analysis Glossary

Explore directors, cinematographers, cameras, lenses, lighting styles, genres, and the visual techniques that shape iconic films.

Explore Glossary →